Before going to Hiroshima, I felt a familiar hesitation – the same one I’d had before visiting Vietnam. The lingering thought that people there really shouldn’t be welcoming us. Americans did something truly horrific to Hiroshima, and it’s hard to reconcile that history with the warmth we felt from everyone we met.

Kana, a woman we met in Tokyo, told us she was originally from Hiroshima. When we mentioned our Japanese itinerary, she warned that there wasn’t a lot to do in Hiroshima, but made us promise to try the okonomiyaki – she swore they do it better than Osaka.

With that in mind, we realized we wanted to see both sides of Hiroshima – we wanted to learn from the past, but we also wanted to experience what the city is currently known for.

We started, as everyone does, at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum & Park.

We started in the museum. It felt right to begin there – to understand the park before walking through it. The museum gives shape to what the open spaces outside represent. It’s quiet, efficient, and devastating. Room by room, the history becomes less abstract: Timelines, models, and artifacts narrowing until you’re standing in front of the human cost.

There are the stories everyone knows in fragments – the flattened city, the flash of light – but what stayed with me were the smaller details. The melted glass bottles. The watch stopped at 8:15. The photographs that make you pause and forget you’re in a museum at all.

It’s called a memorial museum, and that’s exactly what it is – a memorial. You could walk through faster than we did, but it felt wrong to leave someone’s story unread. So we didn’t. We stopped at each placard, each photo, each small object that once belonged to a person who had plans that morning. More than any museum we’ve visited, it demanded that kind of attention.

The only other time we’ve felt something close to that was at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama. Another place built on the insistence that each name, each life, deserves to be read.

One wall carried a quote from Peace Culture vol. 20:

Their hair was scorched and frizzy, their faces, arms, backs, legs – their whole bodies were badly burnt. Blisters had burst and sheets of burnt skin hung from them like rags. The scene through my viewfinder was blurred by tears that streamed down my cheeks. This was hell.

It was the kind of account you can’t soften or distance yourself from. Standing there, I thought about how easy it is, especially from far away, to turn history into a debate or a set of numbers. There are still people who think this attack was justified, or that it could be necessary again. They’re wrong. Irrevocably wrong.

Among all those stories, the one that stayed with me most was Sadako Sasaki and the thousand paper cranes. Unlike so many others in the exhibits, her story extends past the day of the bombing. She survives the explosion as a child and grows up – goes to school, plays with friends – until radiation sickness takes her life years later. The cranes she folded near the end of her life became a symbol of both her hope and the world’s grief.

When we left the museum and stepped into the park, her story was still with us. One of the first things you see is the Children’s Peace Monument, built by her classmates and family. It’s surrounded by glass cases filled with paper cranes sent from all over the world – millions of them. The colors are so bright against the gray monuments that it almost catches you off guard.

From there, the park opens out toward the river and the skeletal remains of the A-Bomb Dome – the one structure left standing near the hypocenter. It’s framed now by the cenotaph, perfectly aligned so that you can see them together: The memorial to the dead and the building that survived.

After that it was time to put Kana’s words to the test. Just down the street from the Peace Memorial Museum & Park is Nagata-Ya (photographed below). We’d read that some people wait over an hour to try their okonomiyaki. Luckily, our wait was only 15 minutes.

We picked Nagata-Ya because of their reviews, location, and the fact that they advertised vegetarian versions. I went for the big udon noodles, Chandler, the thinner, more traditional yakisoba noodles.

Hiroshima’s okonomiyaki looks familiar at first – the same griddled comfort food that’s found across Japan – but it’s built differently. In Osaka, everything goes onto the grill mixed together: Batter, cabbage, noodles, egg, whatever fillings you’ve chosen. Hiroshima’s version, on the other hand, is layered. Each part – batter, cabbage, noodles, egg – is cooked separately, then stacked and finished with sauce. It’s neater, more structured, and you can actually taste each layer instead of one blended whole.

Because we ordered vegetarian versions, they didn’t put any sauce on (as that is typically made with fish sauce). Instead, we got our own vegetarian version that we put on ourselves. Chandler used almost none, while I used a fair amount (although much less than what is typically included!). It was perfect.

Before we left Hiroshima we ate okonomiyaki one more time to make sure our meal wasn’t a fluke. This time we went to Jirokichi (they have a small vegan menu). It was also quite tasty. Though this time we got a bit more sauce than we bargained for!

After all that history, it felt good to see another side of the city.

Hiroshima’s Pokémon Center leans hard into local pride – you can tell the moment you walk in. There’s a Pikachu riding a Magikarp and another Pikachu dressed as a Hiroshima Toyo Carp fan.

We’d actually hoped to go to a Carp baseball game while we were in town, but the team was away that week. It’s easy to see why the Carp matter so much in Hiroshima – they’re one of the few professional teams in Japan not owned by a big corporation, and the city treats them like family. Everywhere we went – from souvenir shops to street stalls – we saw that bright red logo.

There was also a whole set of smaller Pikachus holding on to just as much regional pride.

Pikachu holding a shamoji – a rice paddle – is a nod to nearby Miyajima Island, which is famous for its giant rice paddle (also a floating Torii gate that we’d be visiting later!). Pikachu hilding a lemon, which comes from the nearby Setoda islands, known for their citrus groves. Pikachu holding a momiji manju – a maple-leaf cookie – which is the signature sweet of Miyajima Island (and Chandler’s favorite Kit-Kat flavor!).

I couldn’t help myself, I bought a mini lemon Pikachu plushy to be buds with my sleeping Psyduck. We also bought a metal okonomiyaki spatula (which we hope to one day get the ingredients for!).

After the surprise regional lessons at the Pokémon Center, we made our way to Hiroshima Castle. The original 16th-century structure was destroyed by the atomic bombing in 1945, but the current reconstruction, surrounded by a broad moat and shaded by trees, feels almost timeless. It’s one of the clearest reminders that Hiroshima’s story stretches back centuries.

Like Hiroshima Castle, Mazda feels deeply personal to the city. The castle speaks to Hiroshima’s past; Mazda speaks to what came after.

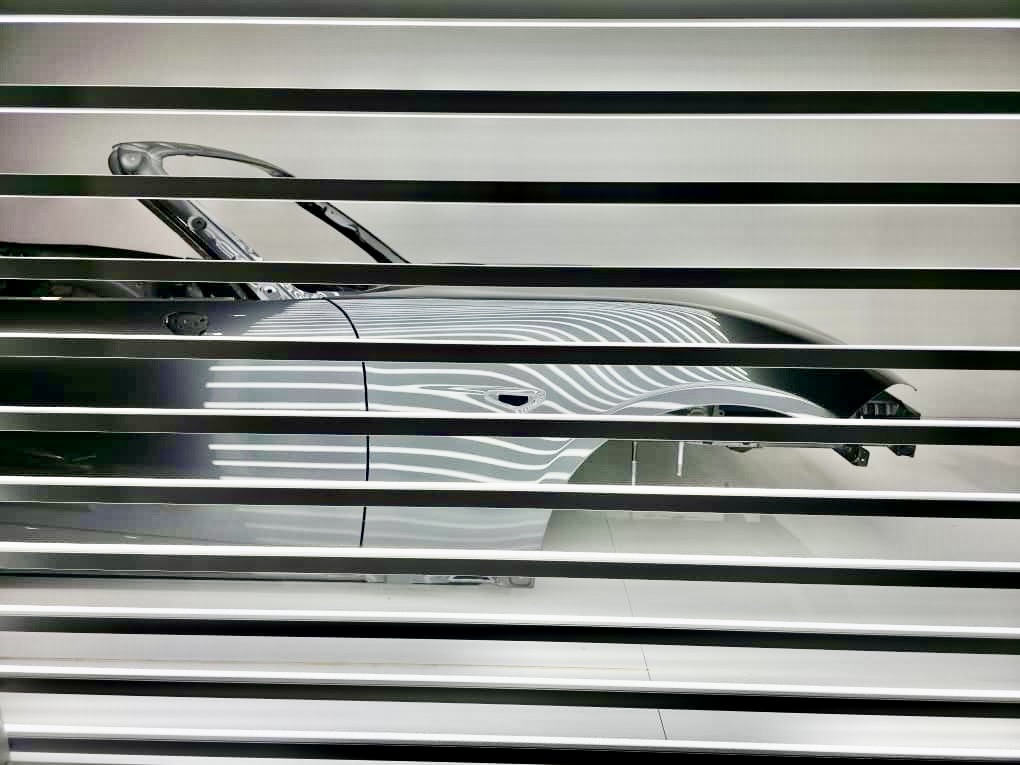

The company’s headquarters and museum sit just outside the city center, on the same grounds where the factory was rebuilt after the atomic bombing. The tour begins with the early three-wheeled trucks – the first vehicles they produced again only months after 1945 to help with the cleanup and rebuilding of Hiroshima.

From there, the exhibit moves through decades of design. The small R360 Coupe from 1960 marks Mazda’s entry into passenger cars. There’s also a rally section, where the 1985 Savannah RX-7 sits with its “Acropolis Rally, 3rd place” sign – more battered and interesting than a lot of the showroom models.

For us, the connection was the Miata. During the two years we lived in the US, Chandler drove one and loved it – and still insists it’s possibly the best driver’s car that’s ever been made. Seeing Mazda’s history laid out gave that affection context. What surprised us, though, was how little attention the Miata actually gets in the museum. It’s one of Mazda’s most recognizable cars abroad, but they mentioned that the vast majority of them are sold outside Japan, mostly to the US.

Instead, the company clearly takes pride in its craftsmanship and safety innovations. A significant number of displays were focused on their signature color “Soul Red Crystal.” They are in love with it, but Chandler and I joke that it looks more like “Old Lady Nail Polish.” It got an upgrade in 2017 and was designed using multiple ultra-thin layers to catch the light on the car’s curves – and is discussed almost as a religion.

One of the final moments on the tour was a view of the shipping area, where finished cars wait to be loaded and sent around the world. If we’d been living in Japan when Chandler ordered his Miata, he would have had it almost immediately. But from here to Dallas took just over a month. Seeing where the cars leave from made the whole thing feel very full-circle.

By then, we felt like we’d been able to see Hiroshima from several angles: History, everyday life, and its economy. So we took a day trip out of the city, not to “escape,” but just to see what was close by. We caught the train and the short ferry over to Miyajima, the island known for the floating Torii gate.

We took one of the morning ferries, partly to avoid the worst of the heat and also because we wanted to see the Torii gate at high tide. Some people prefer to visit (or accidentally visit) during low tide so they’re able to walk out to the Torii gate, but I wanted to experience it surrounded by water. You can actually see the gate from the ferry – albeit from much farther away.

When we got off the ferry, we started walking along the shoreline toward Itsukushima Shrine, but it was already so hot that we changed plans and cut back through the shopping streets. “Alley” isn’t the right word – it’s more of a partially-covered pedestrian street lined with food stalls and souvenir shops – but the temperature was much cooler there.

Deer wander through it the same way pigeons wander through other cities, just part of the background. We didn’t spend long browsing, but we did stop to look at the wooden rice paddles Miyajima is known for. They were invented here as temple tools and eventually became the standard shape for rice paddles everywhere. They’re all over the island – big ones, small ones, painted ones, souvenir ones – all hanging on the walls outside the shops.

As we got closer to the shrine, the landscape shifted. The buildings are set on raised walkways over the water, with lanterns and long wooden corridors leading to the viewpoint for the Torii gate. And behind all that is the mountain – dense, green, almost like a jungle. The contrast surprised me. Photos typically show the gate and the shrine, but not the heavy green rising behind it.

When we reached the main viewpoint for the gate, it was busy, but not overwhelming. The only crowded spot was the area where people line up to take photos. It was an informal system: One couple/group poses, the person behind them in line takes their picture, then the next group does the same. Since we weren’t interested in getting a photo of ourselves with the gate, we didn’t need to wait. Instead, I just stepped to the side and took my photos without having to queue.

Outside of that viewing spot, it wasn’t really packed. There were tourists, but also a school field trip, and everyone was just sort of milling about. If you’re imagining something serene because it’s a shrine, it’s definitely not that. It’s not loud or chaotic, but it’s also not meditative. Still, the view is exactly what you expect it to be: The bright orange gate standing in the water with the shrine buildings stretching out on raised walkways. There are actually a number of other viewpoints throughout the grounds.

On the way back, we stopped for a craft beer at one of the shops – not realizing that there was no seating (or AC!), so we chugged those pretty quickly before continuing on our way. We also bought one of the souvenir rice paddles, but not a full-size one. Instead, we got a small keychain-sized version from a vending machine, which felt appropriately Japanese. They were Toyo Carp themed and we picked number 20 – pitcher Ryoji Kuribayashi.

We couldn’t believe we actually got to choose the player instead of getting a mystery pull! Another surprise was the craftsmanship. Being from the US, we always equate vending machines with low quality, but the quality of this rice paddle was astounding.

Before making it all the way back to the ferry, we realized that while it was not a difficult return to Hiroshima, I would be well past hangry by the time we arrived. Instead, we popped into a restaurant advertising their vegan options and we could not believe our luck. The decor was lovely, but the food was the true star. Our salads were impeccable and the food only improved from there.

We left Miyajima completely satisfied with our day trip – I even found myself petting some of the deer closer to the dock right before we boarded the ferry.

Our time in and around Hiroshima ended up being far more meaningful than we expected. We didn’t stay long, but I’m glad we went. It was the perfect bridge between Fukuoka and Osaka.